This post was updated 24 April 2014

My rating: *****

Note: Simon Coward’s comprehensive, but now defunct, Ace of Wands website (available in the Wayback machine internet archive) and Andrew Pixley’s copious viewing notes which accompany the 2007 Network DVD release have been invaluable in providing background information and quotations for this review.

This British children’s fantasy series is by all current technical standards fairly dire. It is slow, there are noticeable differences between filmed exterior shots, archive stock footage and videoed interior shots as well as glaring continuity errors and booms in shot. The special effects induce hilarity rather than wonder or horror, there are gaping plot holes and dialogue is sometimes stilted. Yet one reads enthusiastic review after review of this series – all of them recent – on the web. Perhaps, it might be argued, that these represent nothing but the rose coloured reminiscences of the legion of nostalgia buffs out there. Yet there are people new to the series, seeing it for the first time (it was made available on DVD in 2007) who are equally keen, even if one admits that those buying such a set are already a specialist audience amongst specialist audiences.

When I first started watching the DVDs I found the stories hideously slow and unconvincing. The special effects (shaking rooms and floating Egyptian artefacts) and faux location shots in quarries were entertainingly amusing rather than gripping. Neither am I a fan of borderline pantomime villains of the type found in The Avengers and the later series of classic Dr. Who. But by the end of the series I was completely hooked. So what happened, what drew me in and kicked all my fan mechanisms into gear? But before talking about that let’s provide some background on the series first.

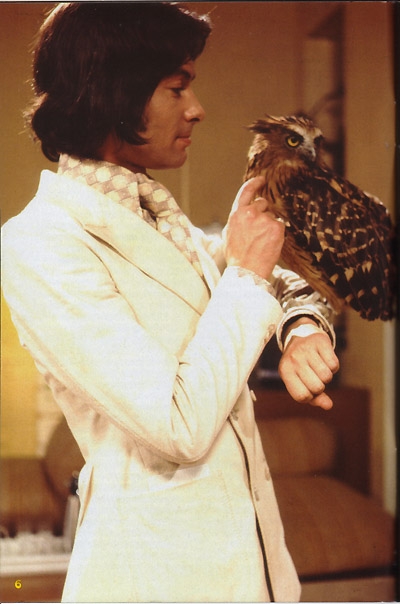

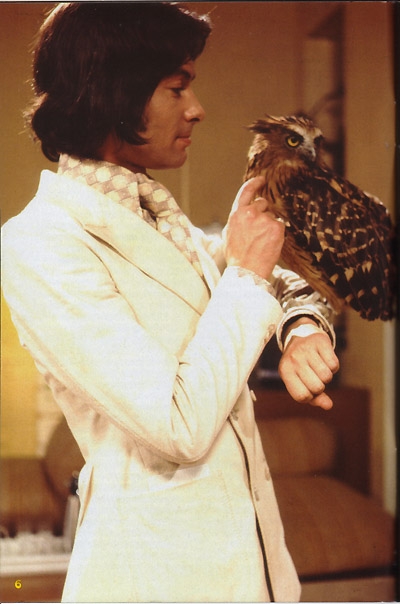

Ace of Wands is a children’s fantasy series originally broadcast by Thames Television from 1970 to 1972. The central figure, Tarot, is a highly successful stage magician and illusionist who, dressed in the height of early 70s fashion and with the help of two assistants/friends (one male, one female), investigates and solves weird goings on. His pet owl, Ozymandias, although not of any practical help in these proceedings, provides moral and aesthetic support.

Three seasons of the series were made and in the historical and cultural vandalism that marked television policies of the 1960s and early 1970s, the first two seasons were wiped by the television company who were out to save money by reusing old videotape. Little did they realise that some thirty years down the track this would be a more than false economy, and that they had unwittingly deprived themselves of a goldmine. There is a lesson in there somewhere. Fans continue to scour the world in the hope that, as with Dr. Who, copies will be found secreted away in the archives of some less irresponsible television station outside the UK.

If these first two seasons ever do come to light, one thing I would particularly like to see is Tarot’s minimalist and futuristic Japanese style warehouse flat. For some inexplicable reason, in season 3 he is moved to a houseboat. I have a serious weakness for futuristic white minimalism and can only see a houseboat as a backwards step in this context.

Perhaps the secret of the series, and what finally engaged my fan interest is the conceptualisation of the central character and Michael Mackenzie’s performance in this role. Indeed the acting all round, of both principals and villains, is very solid which helps make up for other shortcomings. Mackenzie explains the considerable success of his character with the audience at the time, which included not only children but large numbers of university students. Tarot was, he says, ‘a really good looking bloke in attractive trendy clothes of the time – someone the girls like. For the boys he has a pet owl, fast cars and motorbikes’. One might remark, however, that this statement in relation to gender preferences is perhaps unduly limiting. Not a few girls, then as now, tend to look favourably on a man who accessorises himself with fast expensive cars and an animal as exotic as an owl.

In an interview with Simon Coward Mackenzie further remarks on his approach to the role:

I had no idea what I was doing at first, apart from making sure that I looked good in the trendy clothes, fast cars and beautifully designed sets! I thought he should convey the impression of great inner strength and mental and spiritual development but be relaxed. But basically I was so inexperienced I thought it was best to do what I was told by the directors.

He notes elsewhere, ‘I think Tarot is a rather reserved and mysterious person’. In fact we have no background information on Tarot at all and he seems to possess vaguely paranormal powers. A character like this is usually played with a degree of coldness and remoteness, but Mackenzie as well as admirably succeeding in conveying all the character traits he lists above, opts for a warmth and humility which nonetheless, as he says himself, doesn’t preclude Tarot from being a bit of a ‘smartarse’. It is perhaps telling that Mackenzie prefers the episodes penned by P.J. Hammond (of future Sapphire and Steel fame) where Tarot is under genuine threat from adversaries who are far stronger than himself.

There is also a good deal of chemistry between Tarot and his friend Mikki and also it would seem from remarks about the earlier two series, between Tarot and her predecessor Lulli. Nothing is ever stated but perhaps the actors decided that in real life, in non-television land, two people who shared an unusual telepathic link, who embarked on numerous adventures together and who both shared a love of 70s fashion would inevitably get together. We notice Tarot and Mikki flirting quite outrageously sometimes and a discreet physical contact between them that would seem to indicate that offstage in uncensored reality, something was going on that couldn’t be dealt with up front in an early 70s children’s series. Further, as Michael Mackenzie indicates, Tarot had to be seen to be available and unattached to maintain the attention of the female viewing public.

Personally, I have never really understood this argument which is frequently advanced in relation to the depiction of male leads in TV series. From my own point of view, I find it far more interesting to see how my male heroes deal with attachment rather than avoid it or fail to achieve it. It would seem for all these prohibitions, however, that the actors manage to slip the hint of a relationship under the radar and in between the lines. In the DVD commentary tracks Mackenzie and Petra Markham (who plays Mikki) refer to the problematic nature of the undefined relationship in the script, and joke about the flirting between the characters but say nothing about the choices they made in playing the roles at the time.

If Judy Loe (Tarot’s first female ‘assistant’) left the series at the end of season 2 justifiably fed up with, as she says, ‘being allowed some intelligence, but always having to be rescued by the man’, her replacement was given more character scope and freedom. Mikki although sometimes a bit airy fairy and impulsive frequently gets Tarot out of trouble and occasionally initiates an adventure herself (‘The Beautiful People’). It is her brother Chas (Roy Holder) who is the one who usually needs rescuing. This change may have been due to writers such as P.J. Hammond taking over more script control as Trevor Preston, the originator of the series, started to move on to other projects. P.J. Hammond, of course, was to go on to write a wonderful female role (greatly aided and extended by Joanna Lumley’s uncompromising approach) in Sapphire and Steel.

The character of Tarot shares much in common with his contemporary Jon Pertwee’s Doctor in Dr. Who. Both characters have a love for flamboyant 70s fashion – although Tarot’s wardrobe is far more extensive and expensive (!) than the Doctor’s. Both use their wits and intelligence to fight adversaries, even if they can both be irritatingly secure in the conviction of their superior knowledge. Both have mysterious origins – Tarot perhaps more so, as at least we know that the Doctor is an alien from another planet. Both characters also display a warmth and a sympathy towards those around them – even if the Doctor demonstrates an irascibility and impatience that we never see in Tarot. Likewise (unlike David Tennant’s Doctor), they are not willing to condemn their opponents to oblivion. The Doctor is devastated when Unit blows up the Silurian stronghold, Tarot recognises ‘Mama Doc’s’ behaviour as the result of mental illness and arranges some discreet intervention after he has dealt with the main problem. Both characters are also linked in with the ambient early 1970s cultural interest in the ‘mystic East’ and the then trendy interest in the paranormal, the ‘mystical’ and the ‘occult’. These cultural tropes went on to be read very differently in the 1990s during The X Files period.

Most unfortunately, after season 3, in spite of excellent ratings and no sign of a wane in popularity, the series was cancelled, ending on a sudden cliffhanger. The cancellation was due to a change in the directorship of children’s programming at Thames and the series was replaced with the arguably inferior and less subversive The Tomorrow People. One can only speculate on what the series might have become with a couple more seasons, but like so many other promising shows that have been cancelled, we will never know.

The other attraction of Ace of Wands for current viewers is that it is a concept (good looking, mysterious and stylish stage magician investigates weird things with his friends) which still holds up very well today and in this age of the remake and the ‘reboot’, a reactivation of this series could go down very well indeed. (Hint, hint to any program developers out there).

My other posts on Ace of Wands

Ace of Wands (2)

Links to other pages on Ace of Wands

The Ace of Wands website – now defunct but still archived on the Wayback Machine

David Sheldrick

Geoff Wilmmetts

Andrew Screen

Review on the Retro to go site

Mondo Esoterica Review

BFI screenonline page Includes video clips

Pages at Clivebanks.co.uk

My rating: *****

My rating: *****