Most writers struggle to a greater or lesser degree with the blank page. In a newsletter post titled “Perfectionism vs Impatience”, the academic and scholarly writing coach, Jo VanEvery, deals with the difficulty of producing that first draft of writing and refers to the much cited advice to just put pen to paper and write anything no matter how bad and imperfect. The idea is that then you have at least something that can be painstakingly edited and polished to finally produce a refined and well-crafted end product. She uses wood carving as an analogy. From a rough lump of wood still with the bark on, working with ever more refined and sophisticated tools you eventually arrive at a beautiful smooth and polished work of art. [1]

What struck me in VanEvery’s discussion was the idea that it is not always classical procrastination or perfectionism that prevents those first tentative words from being laid down on the blank page, but impatience. Impatience at not being able to produce the well-crafted piece of writing straight away. This impatience is not just something that applies to writing – it also applies to other skills and crafts. How many people would like to play a musical instrument but faced with the arduous and seemingly infinite difficulty of getting beyond those first steps simply cannot stay the distance through that tortuous tedium to arrive at what they hear accomplished musicians producing? Even for the skilled writer, it can simply take too long. There is the research, the formulation of ideas, the structuring and restructuring, the refining of word use to create meaning and style, the search for the right rhythms in phrase composition – all of this takes time and constant re-adjustment. And when writing is only one of the many life jobs on one’s plate, the process seems too stretched out altogether. You just want to see that final product out there, done and dusted, published and added to your cumulative pile of public writing.

This struggle with patience has been no less a factor in the production of this current piece which has gone through multiple restructures, additions and subtractions not to mention meanders down decidedly dubious culs de sac. But this time, armed with the image of the impatient writer, I have tried deliberately, if painfully, to lean into the experience and observe its mechanisms. I am reminded of the famous scene in Lawrence of Arabia in which Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) snuffs out a match with his bare fingers and says “the trick… is not minding that it hurts”. The Mandalorian would add stoically: “This is the way”…

James Horton, a freelance writer and social scientist, very usefully outlines a series of “toxic preconditions” that block writing production and proposes a set of counter-practices. He summarises these toxic preconditions as “misguided beliefs about what writing must be in order to be ‘worth it’”, continuing “If you decide that all of your writing must be important, done once and done right” then you are doomed from the outset. No amount of determined will-power or anxious perusal of self-help literature will drag you out of the hole. [2]

Perhaps, for me personally, one of the most toxic preconditions, a variation on the notion that writing has to be important, is the perceived obligation to be totally original, to be at the avant-garde cutting edge. This of course is a modernist hangover – the idea that one needs to break with tradition and advance knowledge and culture at any cost. Finding that others have already said what you wanted to say – and so much better! – in a world crowded with voices all striving to be heard has an utterly paralysing and silencing effect (I have discussed this in an earlier post.) You have no right to speak unless what you have to say is utterly original and ground-breaking and includes references to every last piece of research in the area. Feeding into this, is the pressure of the academic requirement to make one’s name and reputation and to carve out a unique professional niche. Further added to the mix are the effects of growing up and forming an early career marinated in the extraordinary explosion of new thought and culture that occurred at the end of the Second World War.

Neither should we forget the everyday environmental preconditions for writing. For those employed to write – and let’s restrict the arena to universities here – there are the ongoing and immense pressures to do a whole host of other things (teaching, admin etc.) at a breakneck pace. How can the slow rhythms of writing be accommodated within this setting? There is the additional requirement to squeeze writing into rigid formats such as the peer reviewed journal article, framed within a bureaucratic structure of byzantine reporting processes and metricisation. The latter mechanism banishes the content of writing into the void. Accumulated and carefully categorised publications become mere tokens to be exchanged for other goods such as reputation, job appointments, continued employment and promotion. [3] The overall effect of all this can be utterly immobilising. Now I am no longer in this environment, I can feel the faint stirrings of mobility slowly returning and the frozen tundra gradually reawakening.

But to step back from all this and to turn to the philosophical and existential context of writing practice: what is this strange urge to write? I think here of Foucault’s anecdote about a friend of the painter Gustave Courbet, who would wake up shouting “I want to judge! I want to judge!” [4] I have a similar impulse when it comes to writing, but just like the declaration of Courbet’s friend, “I want to write!” is far too abstract. Write what about what and for whom and why write in the first place? Let’s exclude extrinsic motivations such as the desire to be rich and famous (only achieved by a vanishingly small few), the desire to deliver information, teach or persuade, or to “express oneself” or again, the necessity to write as part of one’s employment or qualification requirements. Let’s take these conditions off the table for the purposes of this discussion and reduce the writing impulse to its most obscurely existential form. Not to write, for those subject to this mysterious drive, provokes considerable malaise. As Foucault notes:

One thing is certain, that there is, I think, a very strong obligation to write. I don’t really know where this obligation to write comes from … You are made aware of it in a number of different ways. For example, by the fact that you feel extremely anxious and tense when you haven’t done your daily page of writing. In writing this page you give yourself and your existence a kind of absolution. This absolution is indispensable for the happiness of the day. [5]

So what do you do with this impulse? The classic writing clichés exhort the aspirant to “write about what you know” or “write the kind of books you want to read”. And there are any number of writing sites and apps providing lists of “writing prompts” each more unbearably insipid than the last. And, as Horton also points out, the old chestnut “just write” is also resoundingly empty – a bit like saying “LOL just win”, shades of the famous Nike advertising slogan…

But perhaps after all, this is all you really have to start with. You can only start by establishing a tentative experimental practice. Begin with a version of free or directed automatic writing practice – such as that engaged in by the surrealists and recommended as a beginner exercise in writing technique handbooks. Then hope that eventually you will see something slowly solidifying and emerging out of the thick fog – a direction, a style, a subject matter, a feeling that the impulse has finally started to carve out a defined track in the wilderness and develop a concrete form. You begin by writing for an audience of one – yourself – then, with the hope that others may find a connection across the network of shared human experience, culture and history, as well as across the broader shared network of non-human existence.

Public writing could be envisaged as a journey for the writer with the goal of providing an artefact for the reader. But the final product only works if the reader has a sense of that difficult trajectory. Writing that is too facile and superficial or too subordinated to an external agenda, that doesn’t involve at least some personal engagement on the part of the writer has little lasting impact on the reader. (Dare I raise the spectre of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Chat GPT at this point?) Foucault introduces the notion of the book as experience, which rather than being a didactic exercise instructing and “teaching” the reader, invites readers instead to make sense of the book and what it has to offer within the context of their own experience and concerns. [6] A reader accompanies the author on at least a part of his or her expedition and launches out onto branching paths of their own. The ultimate value of writing is perhaps in this shared journey along a dusty dirt track laboriously fashioned by the writer out of many detours, dead ends and narrowly avoided precipices.

References and notes

[1] See also Jo VanEvery’s book, The Scholarly Writing Process (A Short Guide), 2016.

[2] With thanks to Oliver Burkeman for this reference to Horton in his newsletter post “Toxic preconditions” The Imperfectionist, 14 March 2025.

[3] See Conor Heaney’s discussion about university work as “meaningless” within the context of neoliberal governmentality. Conor Heaney, ‘What is the University today?’, Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 13 (2), 2015, 287-314.

[4] Michel Foucault. (1997) [1980]. ‘The Masked Philosopher’. In J. Faubion (ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. Volume One. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, Allen Lane, p. 323. For a full quotation of this passage see my earlier blog post.

[5] Michel Foucault, (2004) [1969] Michel Foucault à Claude Bonnefoy – Entretien Interprété par Éric Ruf et Pierre Lamandé, Paris: Gallimard. CD. [This passage translated by Clare O’Farrell] For additional commentary on this passage see my earlier blog post.

[6] Michel Foucault, (2000) [1981] “Interview with Michel Foucault. In J. Faubion (ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Power The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. Volume Three. New York: New Press, pp. 243-5.

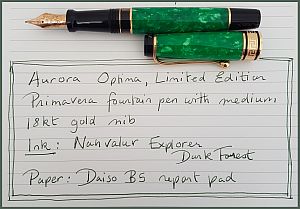

This post was drafted with fountain pen and ink. The pen of choice this time is a lovely green Aurora Optima Primavera, number 2482 of a limited edition of 7,500 fountain pens, manufactured in 1998. It features a variety of subtle design details, for instance two swallows heralding spring engraved into the gold plated clip. Aurora is a high end Italian manufacturer of some quite beautiful and very functional pens. The ink is a very dark green from Nahvalur.