Michel Foucault, Histoire de la folie a l’âge classique. Entretien de Michel Foucault avec Nicole Brice. Enquêtes et commentaires. Diffusion le 31 mai 1961 sur France III National. In Michel Foucault, Entretiens radiophoniques, 1961-1983, Flammarion / VRIN / INA, 2024, pp. 13-16

It seemed to me that madness was a somewhat variable phenomenon in civilisation, It fluctuated just as much as any other cultural phenomenon. Basically, when reading American books about how some primitive civilisations reacted to the phenomenon of madness, I wondered whether it might be interesting to look at the way in which our own culture reacted to this phenomenon. […] There are civilisations which celebrated the mad, others that kept them separate, others that cared for them. But what I really wanted to emphasise was that caring for the mad was not the only possible reaction to the phenomenon of madness. (p. 13)

This interview – the first in the book – was conducted in 1961 after the publication of Foucault’s 1961 book on madness and succinctly summarises the broad arguments of that work.

It’s hard to appreciate today just how novel Foucault’s approach was in the early 1960s. He argued that madness was culturally and historically variable – variations that couldn’t simply be explained away by stating they were pre-scientific and the mere products of superstition and ignorance. “There is no culture without madness” (p. 13) Foucault says, but the way it has been treated across cultures and history differs considerably. Foucault explains he wanted to study one specific cultural and historical instance, namely how madness was conceptualised and dealt with in Europe in the Classical Age (the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries).

What is also clear in this interview – in the light of future misunderstandings – is that Foucault was not arguing that madness was a purely socio-cultural invention. Madness had a physical and real existence – it was a matter of different conceptualisations of a physical phenomenon.

After the “completely free existence” (p. 14) led by mad people up until the beginning of the seventeenth century, the mad, along with other designated social misfits who failed to satisfactorily earn their keep according to the economic notions of the day, were locked up in institutions and made to produce cloth, rope and similar goods. This again proved to be too costly a solution and the institutions were closed down, leaving the mad to occupy these otherwise abandoned social spaces. Eventually we arrive at a culture – our own – in which “the phenomenon of madness has been hijacked by medicine. For us, the mad are mentally ill” (p. 15).

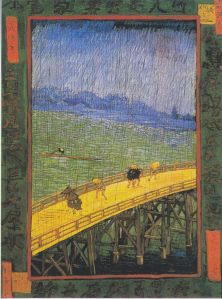

The interviewer finishes with one final left of field question (among others): “Do you think madness is a gift from heaven?” Foucault’s response is a very roundabout “yes”. He argues that in contemporary culture madness has once again become “extraordinarily important”, rediscovering its mission as a bearer of truth (p. 16). He enlists some of his favourite figures in support of his claim– Nietzsche, Artaud, Roussel and Van Gogh [1] – philosophers, writers and artists who were famously mad and who through their work re-awakened the capacity of madness to communicate truth in our culture.

Foucault nuanced, indeed walked back on these claims in his later work. He does this somewhat obliquely as he often did when revising his earlier theories. In this case, he attributes his previously held ideas to the psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers. In a discussion with Tadashi Shimizu and Moriaki Watanabe originally published in Japanese in 1970, he distinguishes his analysis of madness from those of early psychologists Pierre Janet and Théodule-Armand Ribot and in particular from Jaspers, who was still alive at the time of the 1961 interview. Jaspers, he says, discovered what he saw as “the secret code of existence”: “a certain kind of supreme experience” which could only be attained when human existence was threatened by madness. This experience could be found in the work of “Hölderlin, Van Gogh, Artaud and Strindberg”. Foucault then hastens to add: “But my object is totally different”. He explains that the difference lies in his adoption of a strictly historical approach. [2]

A fundamental question in Foucault’s work and one that he continually worked on refining was the question of how truth becomes apparent in and through history. He clearly became aware that proposing a certain essence of madness that escaped history, a unique experience privileged in the way it accessed and communicated truth, a thing that was sometimes visible and at other times hidden, was at odds with the position that truth is embedded and revealed through the general historical process. No one group has privileged access – much as certain far less marginalised groups and individuals would like to claim that they do, using such claims as a basis to exercise power. Foucault of course, examined these mechanisms of knowledge and power at length in his work.

Likewise, there are no periods of history when truth is unilaterally silenced and absent. But again, to add another qualification, this does not mean that truth is wholly contained by history, simply, that there is no way for humans to step outside their existence in history, to access it in another supposedly purer, more fixed form. This inability is not the result of a “fall from grace” either. Following the historian of science Georges Canguilhem, Foucault remarks:

The fact that man lives in a conceptually structured environment does not prove that he has turned away from life, or that a historical drama has separated him from it – just that he lives in a certain way, that he has a relationship with his environment such that he has no set point of view toward it, that he is mobile on an undefined or a rather broadly defined territory, that he has to move around to gather information, that he has to move things relative to one another in order to make them useful. Forming concepts is a way of living not a way of killing life. [3]

This brief interview in the context of Foucault’s later work is a demonstration of his own movement around the territory.

References and notes

[1] The painting by Van Gogh included in this post, demonstrates Van Gogh’s interest in Japanese woodblock prints, in particular those of Hiroshige. These prints had a profound impact on his work. There have been a few exhibitions in recent years which have placed the work of these two artists side by side. For example, a remarkable exhibition at the Pinacothèque in Paris in 2012 which I had the good fortune to attend, and a more recent one in Amersterdam which also very successfully toured Japan. In another instance of the reciprocation of this original cross-cultural exchange, one can refer to a segment in Akira Kurosawa’s 1990 film Dreams, which sees a young man magically transported into the gloriously coloured and textured world of Van Gogh’s paintings in a Paris museum.

[2] Michel Foucault, Folie, litérature, société. Entretien avec T. Shimizu et M. Watanabe, 1970, in Dits et Ecrits, vol II, Gallimard, 1994, p. 108. Item #82.

[3] Michel Foucault, Life, Experience and Science, in Aesthetics, Method and Epistemology. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984. Volume Two. J. D. Faubion. (Ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Allen Lane, Penguin. Dits et Ecrits, nos. #219, #361. For further commentary on this passage see Clare O’Farrell, Michel Foucault, London: Sage, 2005, p. 57.

This post was drafted with fountain pen and ink. This is the fabulously sparkly Benu 2024 Christmas Astrogem, a special edition limited to 500 numbered pens. Benu is a company based in Armenia, originally founded in Moscow. The chief designer has a background in jewellery and art restoration. This time I am using a Jacques Herbin 1670 Violet impérial ink with gold shimmer. This site reviews the ink.

Brilliant!

Adelaide Narrative Therapy Collective http://www.adelaidenarrative.com For bookings and enquiries Adelaide Narrative phone : 046 883 0881 (We apologise that we are unable to answer all the time, please leave a message and we will get back to you when we can). e: info@adelaidenarrative.com

LikeLike

very grateful for these kinds of commentary, still not clear to me (and maybe it was a matter of his evolution) to the degree that MF’s topic was Madness itself so to speak (as a kind of Demi-urge or just natural phenomena?)or a more pragmatist/instrumentalist philosophical anthropology laying out our framings of (institutionalization of) what we treat (and how we treat) as madness?

LikeLike

Hi Dirk, Thanks for your kind comments. I think Foucault’s discussion in History of Madness was taking place at two levels. One level was about the institutional, social and scientific treatment of madness. At a second level he argues for its role as a spiritual reminder to everyone of the limits of human existence. He makes it clear somewhere else that madness is a distinct physical phenomenon and bodily condition not just a social construction – but the question is how is this physical condition interpreted and dealt with in different cultures and periods of history at a variety of levels? I think he is trying to restore to mad people some dignity and social presence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks Clare, I caught some of that in your 2nd piece in this series (not sure what happened to my attempted comment there, some computer/internet issues on my end I think) . The alliance with suffering folks (both from organic and social ills) is admirable and one I’ve taken up in my own work, and the idea of limits of understanding /control is also valuable (John Caputo goes so far as suggesting that MF was creating a hermeneutics of not-knowiing), I do get some sense tho that he (not unlike Deleuze and Guattari) sometimes sees the content of madness as somehow more in touch, more direct/unfiltered, with some underlying reality and that bit seems better left behind.

LikeLike

I agree with this. MF immediately seems to have onto new territory after History of Madness in terms of madness having a privileged access to the truth.

LikeLike

thanks for letting me know Clare, as you note in the 2nd post he’s tricky to follow for a lay reader like myself. I know sometimes the twistiness of Derrida is performative (akin perhaps to showing vs saying) in his early Grammar work but never really had a sense if MF might sometimes be doing something like this as well

LikeLike

I think Foucault’s changes are difficult to follow for everybody! But my sense is that he is always thinking and refining his ideas and coming up with new angles

LikeLiked by 1 person